Should American Progressives Be Calling for a “Public Option” in Banking?

November 30, 2011 | Economics & Trade Politics and Policy Progressive Political Commentary

Proposals for a public banking option are almost unheard of in the U.S., where free-market orthodoxy has, throughout most of our history, held sway over collective approaches to the provision of public and private goods and services. Nonetheless, the concept deserves serious consideration based on the evidence in at least a couple of areas. First, there is the striking success of this model in other advanced and advancing economies for providing and directing lower-cost, long-term capital essential for growth. And second, while better financial sector regulation, oversight, and enforcement might mitigate the worst excesses of an opaque multinational private banking system, it remains doubtful that the resources of regulators can ever match those of the private banking system to circumvent regulations and evade the consequences of wrongdoing. It is now widely understood that the private global banking and financial system has failed to serve the “real” economy, or what we often call, “Main Street.” This is not just the case in the U.S. Europe’s problems, while largely due to an ill-designed monetary union and the high sovereign debt of certain member countries, has been exacerbated by the same short-term-profit-driven, casino approach that has characterized the U.S. financial sector. Perhaps the time has come to consider another model, one that treats banking and finance more like a public utility. A public bank would not have to be beholden to shareholders demanding a 20% annual return. It could circumvent incentives that induce management to take extraordinary risks (cognizant that in the worst-case

Read More...

Why the NAFTA-style Free Trade Agreement Will Fail to Benefit Colombia

October 21, 2011 | Economics & Trade

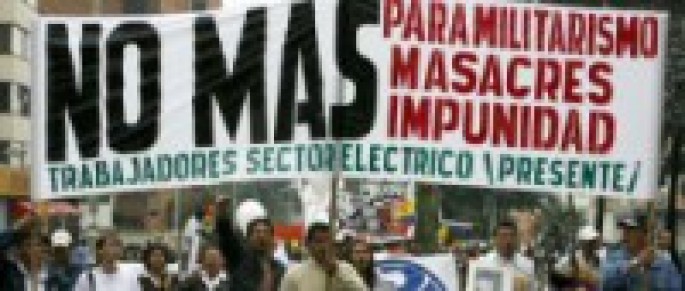

Despite evidence of limited economic welfare benefits and significant social costs, Latin American countries have been signing and ratifying trade treaties with the United States since the early 1990s. This week, the long-stalled treaties with Colombia and Panama were ratified by the U.S. congress and signed by the President. Like other trade treaties, these were based on the same template that has been the basis for U.S. trade policy since NAFTA. In the case of the Colombia Free Trade Agreement (Colombia FTA), promises from the government of President Juan Manuel Santos to better protect trade unionists pressured enough reluctant Democrats to vote in favor of the agreement. Over 4,000 trade unionists have been murdered in Colombia in the past 20 years, mostly by right-wing paramilitaries with links to the government, making Colombia the most dangerous country in the world to support collective bargaining rights. Colombian labor union leaders have rejected government claims that human rights and trade unionist protection has improved, denigrating symbolic gestures aimed at securing U.S. ratification of the agreement, which they rightly claim will help multinational companies over Colombian workers. In addition to doubts that the Colombian government will live up to its promises vis-à-vis the trade unionists, the gains from trade that Colombia can expect once the agreement is in force are ambiguous at best. When the gains to some sectors (e.g. cut flowers, leather goods, seafood, textiles, certain services) are measured against the losses to other sectors (e.g. rice, corn, poultry, communications technology), along with fiscal

Read More...

U.S. Trade Policy and Declining Manufacturing: Where do we go from here?

August 16, 2010 | Economics & Trade

U.S. Trade Policy and Declining Manufacturing: Where do we go from here? By Paul Crist, Aug. 14, 2010 The U.S. economy and the manufacturing sector in particular, face both short-term and long-term challenges. There is debate about whether government can or should play a role in addressing those challenges, and if so, what are the fiscal, industrial, regulatory, and trade policies that would benefit the stakeholders, which essentially include all U.S. citizens in one way or another. I should acknowledge at the outset a bias toward thoughtfully considered government interventions to guide the economy and trade in ways that benefit American workers and allow them to participate in the gains that accrue from their labor. There are economic reasons for my bias that have nothing to do with either socialist or altruistic impulse. That bias in no way means that I favor protectionism or a retreat from global trade, or that government intervention in the economy is always desirable, but there are, I believe, issues and stakeholders that get too little consideration and solutions to structural economic problems that are given short shrift in the name of conservative ideological orthodoxy. There is ample evidence that without adequate and well-designed regulatory intervention in domestic and global markets, capital and political power tends to migrate upward and become concentrated at the top of the economic ladder. We see that phenomenon in country after country, most recently in the U.S. Concentrated wealth becomes problematic when it undermines social cohesion and a sense of

Read More...

America’s System Failure: Only a Wave of Democratic Participation Can Save This Country

August 8, 2010 | Paul Crist Politics and Policy

I didn't write this... but posted it because it is well worth reading! America's System Failure: Only a Wave of Democratic Participation Can Save This Country As welcome as it was, the removal of George W. Bush was not enough to cure what ails us. It goes to the root of our political system. by Christopher Hayes February 3, 2010 There is a widespread consensus that the decade we've just brought to a close was singularly disastrous for the country: the list of scandals, crises and crimes is so long that events that in another context would stand out as genuine lowlights -- Enron and Arthur Andersen's collapse, the 2003 Northeast blackout, the unsolved(!) anthrax attacks -- are mere afterthoughts. We still don't have a definitive name for this era, though Paul Krugman's 2003 book The Great Unraveling captures well the sense of slow, inexorable dissolution; and the final crisis of the era, what we call the Great Recession, similarly expresses the sense that even our disasters aren't quite epic enough to be cataclysmic. But as a character in Tracy Letts's 2007 Pulitzer Prize-winning play, August: Osage County, says, "Dissipation is actually much worse than cataclysm." American progressives were the first to identify that something was deeply wrong with the direction the country was heading in and the first to provide a working hypothesis for the cause: George W. Bush. During the initial wave of antiwar mobilization, in 2002, much of the ire focused on Bush himself. But as the

Read More...